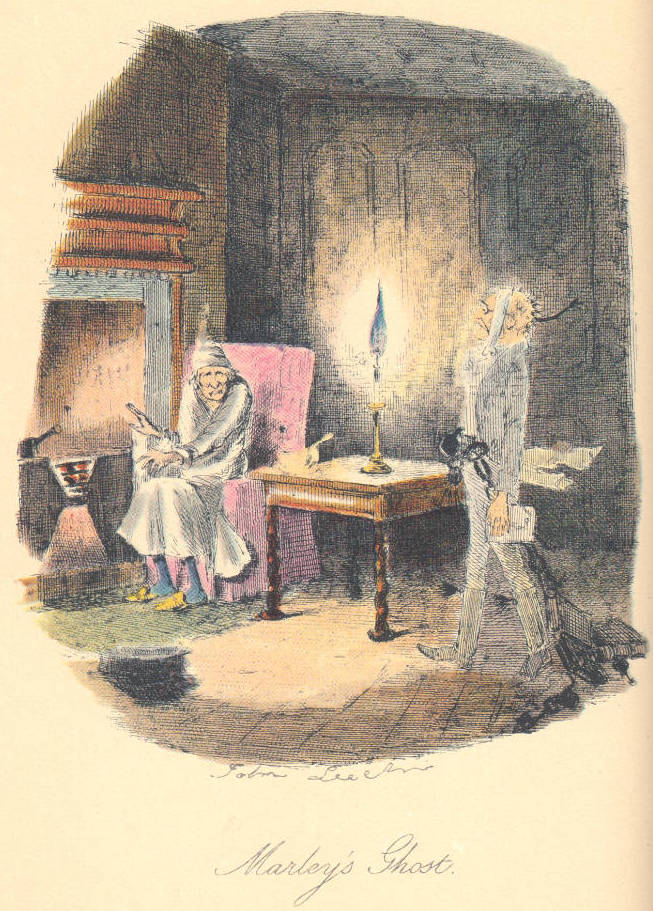

Marley was dead to begin with. There can be no doubt whatsoever about that.

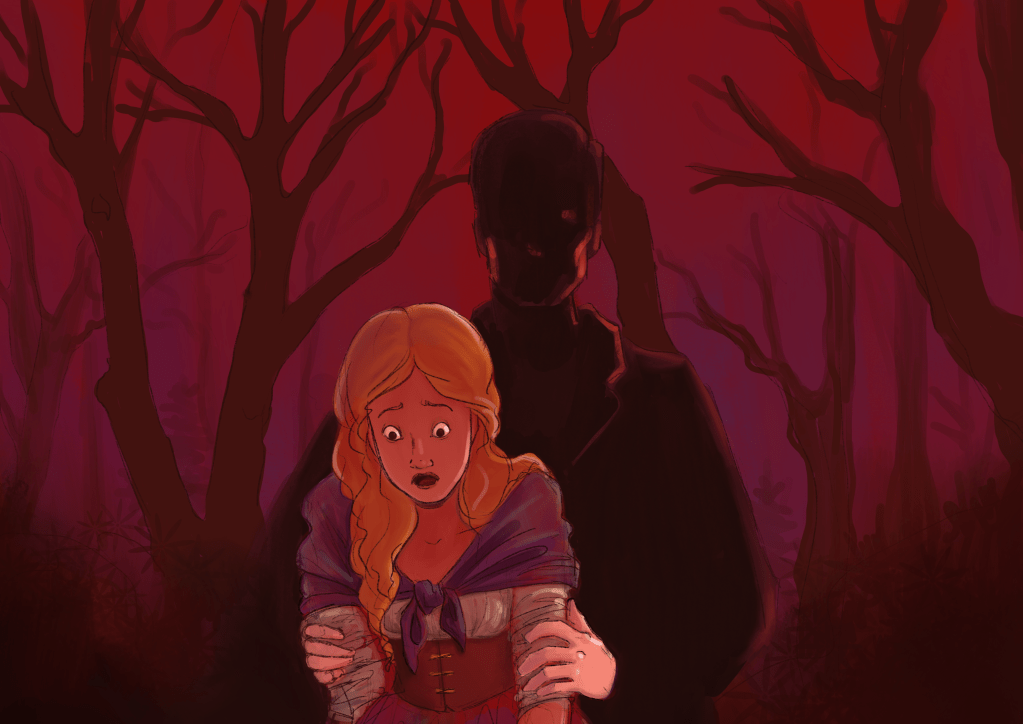

And with those immortal words, generations have settled in to embrace the spirit of Christmas — with ghosts. I know very few people1 for whom A Christmas Carol is not an integral part of their idea of the holiday itself. Whether their introduction to it was the text itself, the Muppet version (which actually does include a surprising amount of Dickens’ own words), or any of the myriad other forms and adaptations, its depictions of family and friends getting together in joy, its message of compassion and good will to all mankind, even its nineteenth century trappings of geese and pudding and silly games have all become the markers of the season and the holiday. Yet, for all its good cheer, it is emphatically a ghost story — and a creepy one at that!

Think of the scene when Scrooge, alone in his darkened rooms, hears the sound of Marley’s ghost coming for him:

Continue readingAfter several turns, he sat down again. As he threw his head back in the chair, his glance happened to rest upon a bell, a disused bell, that hung in the room, and communicated for some purpose now forgotten with a chamber in the highest story of the building. It was with great astonishment, and with a strange, inexplicable dread, that as he looked, he saw this bell begin to swing. It swung so softly in the outset that it scarcely made a sound; but soon it rang out loudly, and so did every bell in the house.

This might have lasted half a minute, or a minute, but it seemed an hour. The bells ceased as they had begun, together. They were succeeded by a clanking noise, deep down below; as if some person were dragging a heavy chain over the casks in the wine-merchant’s cellar. Scrooge then remembered to have heard that ghosts in haunted houses were described as dragging chains.

The cellar-door flew open with a booming sound, and then he heard the noise much louder, on the floors below; then coming up the stairs; then coming straight towards his door.