This is a review literally years in the making. I first listened to the audiobook1 back in, I believe, 2020 when it first came out, and I am not sure I can adequately convey how enthralled I was. I listened to it at home — alone in the kitchen, making tea, or outside shoveling snow off the front walk. I listened at work, alone in the otherwise darkened bookstore before we opened, or in the back office while I stared at spreadsheets and inventory numbers. When I was out front, doing the customer service parts of my job that could not be done while wearing headphone, I resented having to tear myself away. And, when it was finally over — in all its hair-raising, satisfying glory — I felt slightly at a loss for how to fill the silence. I missed the characters and the place and the cadence of the actors’ voices. So I started it again. I am, admittedly, the sort of reader who can truly fixate on stories that appeal to me, and this novel brought it out in all the best ways.

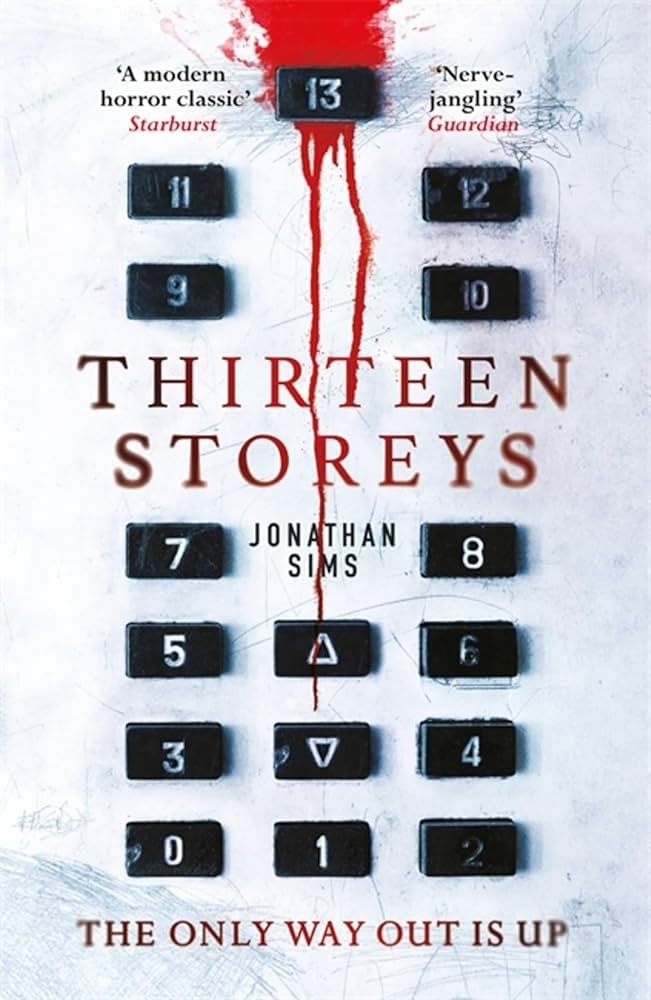

The conceit of Thirteen Storeys is more or less a simple one: an infamous, reclusive billionaire died under mysterious circumstances at a dinner party in his penthouse at a luxury tower block, and none of the thirteen guests — a random assortment of people related to the building, including a small child — were ever arrested for the murder. The novel then offers a series of interconnected horror stories about the guests and the building, culminating in the event itself. This brief description in no way does justice to the brilliance of the book. As with anything, stripped down to its bare bones, it sounds plain and almost derivative. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Before we go any further, I should preface this review by pointing out that Thirteen Storeys comes with every non-sexual content warning you can possibly think of. That said, it is worth all of them. So, gird your loins, and let us proceed.

Our starting point must, of course, be the setting. Banyan Court is a luxury apartment complex built in the center of London’s Whitechapel neighborhood.2 As one character observes: “There it stood, a bright splinter of excess, burrowed into the grey and dying streets of struggle and hardship, unable to even admit the parts of itself it considered shameful. Aesthetically, it was acceptable. Conceptually, it was art.” The building itself is not immune to the hardships baked into the environs. Local guidelines require that there be a section of low-income housing, which is cramped and subpar and heavily segregated from the shining front facade. You could argue that it’s a bit heavy handed, but gentrification is like that in reality, too, so it never feels like it does not work.

All of our characters live or work in Banyan Court, the drama all takes place within its walls and comes from the way that the horrors that allowed for its construction have tainted the very soul of the building. Rather than being a character itself, Banyan Court becomes a funhouse mirror that reflects and distorts the residents fears, guilts, and insecurities back at them. Even more importantly, each of them has something that reflects and amplifies the voiceless victims of the Fell family pursuit of fortune.

Our protagonists are an interesting range of characters — a young woman determined to work hard and prove herself, a self-impressed art dealer, a solipsistic tech guru, a little girl with an imaginary friend, a struggling law clerk, an exhausted and insomniac single mother, a disheartened aspiring writer, an exasperated estate agent, a businessman being overwhelmed by a scandal, a resentful concierge, a very competent and observant plumber, and a young man dealing with trauma from past substance abuse and homelessness. All of them are unique, interesting characters who will subvert your expectations of their basic descriptions. Jonathan Sims is never afraid to let them be human and flawed and even, in places, deeply unlikeable. After all, it is usually their flaws that leave each of them open to a different type of haunting, and allow them to be the correct conduit for each ghost.

The ghost themselves are a refreshingly unique bit of writing as well. Thirteen Storeys treats us to a variety of manifestations an horrors. Some of the stories have figures that could be viewed as traditional specters, both individually named and otherwise. Some characters find themselves possessed by ideas and compulsions they can’t escape. There is (presciently, it would seem) an overzealous AI. A creepy television program haunts a woman’s dreams. Sins from the other side of the world and from the history of the neighborhood imprint themselves onto the psychic and physical landscape. The building itself shifts and changes, breathes and bleeds. It traps and changes the characters in ways that they would not know how to ward off.

And, here’s the most striking thing — while there are many, many moments throughout the book that are disturbing or unsettling or outright scary — the most lingering impression is one of sadness. Isolation and privation and fear and all of the things that offer hauntings are sad. Ghosts, done right, are heartbreaking. Here, they are definitely done right.

Each of the stories can stand on its own merit, but they are best in constant dialogue with each other. You get little glimpses throughout of the ways their lives and stories are interwoven, how they intersect and bounce off of one another. And, of course, the final chapter is the culmination of all of the stories — you need the aggregate effect for it to land properly. A final chapter that can see you recoil in revulsion, weep with poignancy and relief, and grin at the justice of its resolution is a masterpiece, and the bloody climax offers a deeply satisfying catharsis that ticks all of those boxes.

Some of Jonathan Sims’ themes and preoccupations from earlier works make a reappearance. These range from visual notes like changing hallways and uncanny others to more conceptual ingredients. Here, we once again see him contending with the heaviness of loneliness and isolation, with economic disparities, abuses of power and the institutions that uphold them. There is another rich and powerful antagonist who will go to horrifying lengths to use the people around him to suit his own ends. Again he explores the way we frame who gets to tell a story, and the way some people are treated as invisible or disposable to the narrative. All of these are threaded expertly throughout the stories; and practice has clearly helped clarify and strengthen his approach to those themes.3 It is a searing indictment of capitalism, but also an affirmation of human care.

Now feels like a good moment to highlight the audiobook specifically. It is recorded with a full cast, which in this case means the a different actor reads each story. They all do a fantastic job. They read clearly, but with nuance and emotion that brings a great deal of life to the characters. The sound design is minimal, rather than over-produced — I have definitely heard adaptations of horror novels in the past that try too hard, with an end result that is corny and messy. Thirteen Storeys sidestepped the temptation, and lets the narration shine in its own right. It is, perhaps, a little cluttered in the final chapter when the narration switches between the voice actors throughout the final act, but it works.

There is a lot more that I want to say about this book, and so many details I want to point out. I want to dig into the intricacies of the world building and character pieces; highlight its quiet, stirring moments. At the same time, I don’t want to give away too much or ruin the experience of the narrative. You need to let it unfold in its own way, and at its own pace. You need to be unsure at first, to see more and more of the pieces (hopefully less obsessively that Cari or Gillian or Damian), until the picture finally comes into full view. However, once you’ve read it, or if you’re the type to enjoy spoilers, here are a few details that I really appreciate:

(Spoilers below)

- That Edith and James matter. Are, in fact, pivotal, rather than just being fodder for the advancement of the plot.

- On the same note, that everything matters. All of them are intertwined, and humanity matters. They are stronger together, which is always one of my favorite themes.

- How deeply sad and poignant Penny is as a figure, and the depth of Anna’s sympathy for her, even if she is too young to fully understand that her “imaginary friend” is the ghost of a child who died of famine, and has become something twisted.

- The annoyed resignation with which Janek faces blood coming out of the taps truly delights me.

- That no one ever misgenders Damian, not even the villain. Some authors would definitely use that in places where a character is being threatened, and I love that it never happens here.

- How gleeful I felt when Donna stopped Tobias Fell from calling the cops.

- “Eat the rich” being literal and horrifying, and the detail of Anna being too young to get it so just going right ahead.

- That Jason is the first one to say “no.” Regardless of his failings and posturing leading up to then, he is brave enough to do that.

- How deeply satisfying and cathartic the moment of justice is

- Violet and Cari ending up together, and Damian being an important part of their lives.

- The sentence “Listen in the dark, and follow the music.”

(End of spoilers)

I have often been told that no piece of art deserves a perfect review, and I agree that there is value in clear-eyed discussion and critique even of things you love. Contrariwise, I also think that we sometimes forget how much pleasure can come from just enjoying a work, not tarnishing it by digging deep for ways to force dissatisfaction. And I definitely gain a great deal of enjoyment from Thirteen Storeys. Listening to it again this past week, after more than two years since first diving into it, I once again found myself transported, eyes tearing and heart pounding, and did not have it in me to resist.4 The truth is simple: Jonathan Sims is a brilliant writer, the cast of the audiobook are all fantastic storytellers, and this is one of my favorite collections of ghost stories. Just go read (or listen to) it already.

- Amusingly, I don’t actually listen to audiobooks all that often. Podcasts? Definitely. Audiobooks? Sometimes, but I usually find them off-putting for fiction. I do know that I pre-ordered the print edition of Thirteen Storeys as well, so am at a loss to remember why I went this route. That said, I am very glad that past me made the decision to listen to the audiobook. ↩︎

- Characters within the novel share frustration over a pet peeve of mine: there is much more to the history of Whitechapel than Jack the Ripper. There is a lingering, prurient obsession undercut with smug moralizing that really bothers me where that case is concerned. Also, if you really want to be ghouls, they were not even the most disturbing murders to plague London in the summer of 1888. ↩︎

- Every author grows and matures the longer they write, and I love the chance to witness it happening in real time — particularly with a writer whose starting point was already excellent. It is not a surprise, I think, that I am a fan of both The Magnus Archives and The Mechanisms. The former, while being one of my favorite podcasts, does have some of the inconsistencies that come with serial, episodic works. Which is not a complaint, merely an observation. I have both praise and criticism for MA that I will eventually address in a separate article. I will likely never write about The Mechanisms for two reasons: 1) they offer the immediate nostalgic serotonin boost that comes from tapping into my college self’s love of steampunk cabaret and the attendant scene; and 2) music is a special magic that I cannot fairly intellectualize without historical context as framework. Also, it only tangentially ties into the themes of this blog. ↩︎

- In the spirit of fairness, I will offer one tiny comment to mollify the critical school: Jonathan Sims tends to use the word “disorientate” in place of “disorient.” While I am aware that common usage — and particularly common usage in the UK — dictates that this is perfectly correct, my extreme dislike of the word is the one bit of pedantry I allow myself. I find it jarring anytime it occurs. This is a non-complaint, and I am entirely satisfied with that. ↩︎