“Come listen to my story,” the song starts. “I’ll tell you no lies.”

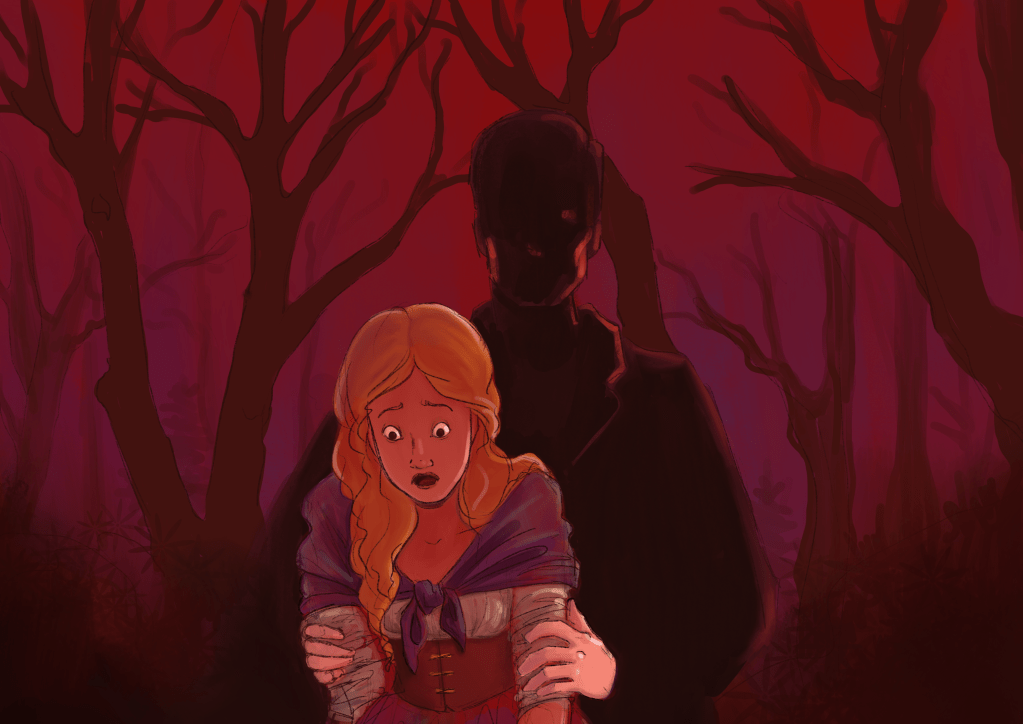

The scene unfolds: a beautiful young woman steals away into the woods at night. The branches creak overhead, the river rushes somewhere through the trees, and the figure of a man beckons her to an open grave or a watery death. In the dark, the wild birds sing.

It is, as they say, a tale as old as time; one that we have seen play itself out in countless fairy tales, ghost stories, plays, true crime podcast, and — yes — ballads. You may have heard the term “murder ballad” before. But what does it mean? As Madison Ava Helm wrote in the introduction to her thesis on the subject: “The ballad is a tricky minx to categorize.”1 Bear with me, and we’ll do our best.

Originally, the word ballad comes from the French chanson balladée, or “dance song,” though time and practice in English have diverged from that definition. The Oxford English Dictionary defines a ballad as: “a poem or song narrating a story in short stanzas. Traditional ballads are typically of unknown authorship, having been passed on orally from one generation to the next.” Murder ballads more specifically are narrative songs from the folk tradition that deal with untimely death — and usually the death of women.

With the release this year of Beyonce’s Cowboy Carter, murder ballads are becoming a little more well-known outside of the niche sphere of folk music.2 This is no bad thing. The survival of folk stories and folk traditions has always been ensured by their adaptability, by the way they shift and change and find new resonance in new ears and stories. To quote Maria Tatar: “Fairy tales are always more interesting when something is added to them. Each new telling recharges the narrative, making it crackle and hiss with energy.”3

Take the familiar tale of Little Red Riding Hood. A little girl travels through the woods to visit her grandmother. In the forest, she meets and converses with a wolf. He races ahead to reach her grandmother’s house before her, consumes the old woman, then lies in wait for the girl to arrive. When she does, the wolf eats her too. Originally, that is where the story ends. Later versions of the story let them be rescued, and even take revenge. Later still, Stephen Sondheim has her survive and wear a wolfskin cloak as she takes on further calamities in the woods.4 But the framework and the message are still there: beware of entering the woods. Beware of who you trust, and what you offer, once you’re there.

This basic shape can be found in many classic folk stories and fairy tales. We see it in Reynardine, wherein a young woman in the mountain woods meets and converses with the charming Reynardine (who, depending on the tale, is a man or a fox or both). He invites her to his castle, and there she meets an ambiguous end.5

In The Fitcher’s Bird, a sorcerer takes the form of a poor man, and steals young women, who are never seen again. Eventually, he sets his sights on three sisters, and brings them — one by one — to his home in the woods, where he marries them. He gives his wife an egg to carry, and then, like Bluebeard, he forbids them entry to a certain room in his house. I think you can safely assume what happens to them when they give in to their curiosity. The third sister finds her dismembered sisters in the chamber, and their souls warn her of what is to come. In some versions, she reassembles them there and they come back to life. In some, she hides their limbs in a basket to return them home. Either way, she disguises herself to escape her husband’s home, and brings the village back to deal with the danger in the woods.6

There is a dangerous, gothic dreaminess to fairy tales that is difficult to describe. It is a strange combination of the prosaic and the uncanny, of danger and warning. Often they take place in the woods, which are portrayed as a liminal space, not bound by the laws of the town. The fairy tale forest offers danger, uncertainty, and change. A lot of it is based in a feeling. As the saying goes — I know it when I see it. Which brings us full circle to a place where we can definitely see it: in murder ballads.

This style of song can be found in multiple cultures, particularly those linked to the British Isles, offering us stories of grief and violence that have been passed down through many eras. There are echoes of it in everything from movie soundtracks to metal albums, but nowhere seems to have such a visceral claim on the genre as America — and specifically southern Appalachia. Mention murder ballads, and the first sound that will spring to mind is fiddles and banjos; the first image, an imaginary version of the mountains of North Carolina. As Christina Ruth Hastie wrote in “This Murder Done”: “The songs allow for a specific reading of Appalachia as a kind of borderland.”7 In this scenario, the entire region becomes the forest of Perrault and the Grimms.

But 19th century Appalachia was a real place, with a real tradition of musical storytelling. To again quote Hastie, murder ballads became popular “at a time of great industrial and economic growth in the eastern United States,” and “represent a regional response to emerging ideas that infiltrated even the most rural parts of the country.”8 As the idea of cultural identity shifted, creating an existential tension, people sought out stories that felt and sounded like their idea of themselves, and had clear lines and morals. This was equally true of the concurrent boom of Romanticism (and interest in fairy tales) back in Europe, where changing borders and concepts of nationalism made people look for a regional identity. This was useful both from the inside and the outside of each place as a way of dealing with uncertainty.9

Mae Miller Claxton spoke to Ron Rash — an author and professor of Appalachian Studies from North Carolina — about the prevalence of violence in stories from the region. “On some level we all have our crimes, those we inflict and those we endure,” Rash said.10 He later continued: “The idea of “justice” is a huge part of literature, because often literature is about when the accepted forms of justice don’t prevail, so sometimes another kind of justice comes in, as in Antigone.”

The earliest murder ballad known to specifically come from Appalachia is “Omie Wise.” Poor Omie is lured into the woods by John Lewis, who promises her “money and other fine things,” but instead murders her.

He kissed her and he hugged her then he turned her around

And pushed her in deep waters where he knew that she would drown

He jumped on his pony and away he did ride

As the screams of little Omie went down by his side‘Twas on one Thursday morning, the rain came pouring down

When the people searched for Omie but she could not be found

This becomes the model for an entire subgenre of murder ballads: the murdered sweetheart. In each, a beautiful young girl is lured away and killed by her lover. Sometimes justice is done. Sometimes it is not.

Naomi Wise was, in fact, a real person. A teenaged orphan in early 19th century North Carolina, Naomi Wise already had two children from separate fathers when she became romantically involved with a seemingly respectable man by name of John Lewis. Once again, Naomi became pregnant. Her lover promised to meet her in the woods, either to sign bastardy bonds (an early version of child support) or to marry her. Instead, he drowned her in the Deep River. Her body was discovered some time later.

We will hear this story again, in an only slightly different key.

In England, twenty years later, we find another woman in the mold of Naomi Wise. Her tale, as told by Judith Flanders, goes like this: “Maria Marten was the daughter of a mole-catcher in Polstead, a small Suffolk village. She was no better than she should be, having had two illegitimate children by two different men. A third man, a farmer named William Corder, was her current companion, by whom she had a third child. This time she was pressing for marriage. She was last seen in May 1827, heading to meet Corder at his barn on her way to Ispwich to be married. … Eleven months after the supposed marriage, her father found his daughter’s remains buried in a shallow grave in the Red Barn.”11

Maria Marten and her murder became one of the biggest stories of nineteenth century England, filling newspapers and inspiring endless melodramas and penny dreadfuls and broadside ballads. As it grew, it underwent the same transformation as the murdered girls in Appalachia: Maria became the wide-eyed innocent, Corder the Bluebeard tempting her to her death. While only two scripts of the many productions of the Murder in the Red Barn survive, we still know the story, and it continues to inspire new works.

As recently as 1992, Tom Waits recorded his own “Murder in the Red Barn,” adding to the library of murder ballads with yet more gothic imagery:

Now the woods will never tell

What sleeps beneath the trees

Or what’s buried ‘neath a rock

Or hiding in the leaves

‘Cause road kill has its seasons

Just like anything

It’s possums in the autumn

And it’s farm cats in the spring

There was a murder in the red barn12

William Corder was arrested, tried, and convicted for the murder of Maria Marten. One of the most interesting details of the story and the trial addresses the discovery of the murder. Maria Marten’s stepmother testified that she had dreams of Maria’s ghost, showing her to the grave. This little glimpse of superstition just adds to the neat tying-off of the tale.

There is no proof that John Lewis ever stood trial for his murder of Naomi Wise. The closest historians can find is evidence that he was charged over his brief escape from law, but largely he seems to have escaped justice. In 2013, the band Vandaveer released a version of “Omie Wise” that offers a small measure of closure in a bit of poetic justice:

They sent for John Lewis to come to that place

And they brought her but before him so he might see her face

He made no confession but they carried him to jail

No friends or relations would go on his bail

John Lewis escaped from the Carolina county jail

And he fled for Kentucky on his way to hell

Death came a-calling ten years to that day

John Lewis fell ill and he met his rightful fate13In some ways, the persistence of the ballad, forever linking his name with the murder, is the main justice offered to the woman he tried — and failed — to erase from the public eye.

Then, there is the strange shift in emphasis that is the song “Poor Ellen Smith.” The most common version of this ballad is situated when the murderer — never named in the song — has already been arrested, and is awaiting his execution. It begins with a strangely passive description of finding her body: “shot through the heart, lying cold on the ground, her curls were all matted, her clothes scattered round,” before changing perspective to her surprisingly penitent killer awaiting execution.

At night, I see Ellen and cry bitter tears

The warden just told me that soon I’d be free

To visit her grave under that old willow treeI’m going to Winston, I’ll stay there a year

It’s often I think of sweet Ellen so dear

Poor Ellen Smith, how was she found?

Shot through the heart, lying cold on the ground14

The real Ellen Smith seems to have been a biracial woman in Winston-Salem, North Carolina,15 who had an affair with a white man named Paul DeGraff. “A combination of court testimony and letters between the two suggest that Smith became pregnant with DeGraff’s child, and left Winston-Salem with the intention of giving the child to her mother to raise. Smith’s baby died soon after birth, and Smith returned to Winston-Salem, and to DeGraff. DeGraff both admitted to and denied being the deceased child’s father depending on who he spoke to. Regardless, Smith still seemed to love him, and DeGraff tired of it, so he killed her.”16

For all of the strangeness of the ballads based on the tale17, they miss out on one of the most interesting aspects of the legends that grew up around the trial itself. Tradition holds that the ghost of a murdered person can be summoned at their grave — but only by the murderer. So stories claim that when DeGraff was found at Ellen Smith’s grave, he was interrupted in the midst of the ritual that would allow him to beg her forgiveness. Either way, he was arrested, tried, and executed, to be forever remembered in song as a penitent killer.

Articles and discussions often relate murder ballads as being an early incarnation of “true crime” — and these origin stories do seem to support that — but in many ways that feels as though it misses the mark. While true crime is also built around a forced narrative framework, picking and choosing how to portray a given story, a given murderer or murdered girl, its main conceit is truth. Murder ballads go almost the opposite way. They drop the facts and the semblance of truth to find the older story beneath. They bring them back to being fairy tales. Our murdered women all become Red Riding Hood. Their murderers, whether they are named Willie or John or Reynardine, all become the Wolf.

Perhaps the largest difference between the two forms of media is how we let the women speak. While the women in fairy tales often have a supernatural chance to call out their murderers after their deaths, to even exhort others to avenge or revive them, the majority of the Appalachian ballads leave the women voiceless, save for the music itself. The songs become a ritual of memory and warning. “In many ways, the murdered girls never die, as we continually revive them within the ballads; conversely, the women are always dead, and we kill them again with every performance.”18 They are stuck forever haunting the line between life and death, the Fitcher’s wives attempting to warn their sister before it’s too late.

It is also worth remembering that plenty of the murder ballads are just stories, with no apparent link to factual events. A perennial favorite, with an abundance of eerie imagery is “Pretty Polly”. Rennie Sparks wrote about the song, saying: “The first time you hear ‘Pretty Polly,’ you giggle nervously. The dark forest flowing with blood, the beautiful girl, the open grave – it makes you dizzy with a strange mix of horror and delight. The flat, vaguely medieval melody circle and drones. The chant rises in fury as the words round their dusky path. Cryptic signifiers flash through your head – red blood, white skin, dark grave. … Alternate lyrics and melodies crisscross the lines between one tragedy and the next, but Pretty Polly separates herself from the other lost beauties by two strange things – a grave dug the night before, and the call of wild birds.”19

The ballad tells of a sweet girl named Polly (a common name in ballads), in love with a man named Willie (also an exceedingly common name), who exhorts her to “come go along with me, before we get married some pleasures to see.”

Oh, he led her over mountains and valleys so deep

He led her over hills and valleys so deep

Polly mistrusted and then began to weep

Saying Willie, oh, Willie, I’m afraid to of your ways

Willie, oh, Willie, I’m afraid of your ways

The way you’ve been rambling you’ll lead me astrayOh, Polly, Pretty Polly, your guess is about right

Polly, Pretty Polly, your guess is about right

I dug on your grave the biggest part of last nightShe knelt down before him and what did she spy

She knelt down before him and what did she spy

A new dug grave with the spade lying by20

She begs him to spare her life, but he stabs her in the heart before putting her in the grave, “leaving nothing behind but the wild birds to moan.” It is one of the most atmospheric and evocative stories of all the ballads — and it comes with its own horrific warning: being virtuous is not guaranteed to save you. And yet, we love the frisson of delighted horror that goes up our spines at the grim imagery of the waiting grave in the woods.

The nineteenth century saw a boom in sensational stories about murder and death that far outstripped the actual incidence of violent crimes tried by courts. The public imagination lusted for the shiver of fear and titillation that came with illicit acts and their bloody ends — but they also wanted their stories to have resolutions. Fairy tales came packaged with tidy morals. Melodramas with punishment of the guilty. Even in reports of actual crimes, exaggeration and outright fabrication often offered laments and admissions of guilt to make the narrative safer. We turn things into stories to make sense of them, to make them safer. In many ways, there is nothing more narratively frightening than Iago’s “What you know you know.”

Fairy tales and ballads alike are cautionary. They tell us to be wary of following another into the woods, even (especially) someone we love. If we are lucky, we will come out of our encounters there like Sondheim’s Little Red Riding Hood — knowing things we hadn’t known before, but ultimately alive. But only if we’re lucky.

- “I’ll Tell You No Lies”: An Exploration of Trauma, Memory, and Violence in North Carolina Murder Ballads, Madison Ava Helm. Read it here. ↩︎

- Even LitHub published a fun article about Cowboy Carter and the tradition of murder ballads. ↩︎

- from the introduction to The Cambridge Companion to Fairy Tales, edited by Maria Tatar. ↩︎

- Angela Carter’s version of the Little Red Riding Hood story, “The Company of Wolves”, goes in an even more radical direction: her girl avoids being consumed at all by instead seducing the wolf. Who has already killed her grandmother. ↩︎

- The Carolina Chocolate Drops have a gorgeous ballad version called Reynadine. Who can resist listening to the amazing Rhiannon Giddens? ↩︎

- The Fitcher’s Bird, by the Brothers Grimm. There is also a wonderful album by Forest Mountain Hymnal called The Fitcher’s Bird and Other Tales of the Macabre that starts with a song based on the story. This same album has a version of “Pretty Polly,” which we discuss later on. ↩︎

- From “This Murder Done”: Misogyny, Femicide, and Modernity in 19th Century Appalachian Murder Ballads by Christina Ruth Hastie. Read it here. ↩︎

- From “This Murder Done”: Misogyny, Femicide, and Modernity in 19th Century Appalachian Murder Ballads by Christina Ruth Hastie. ↩︎

- The Brothers Grimm and their contemporaries collected German folk songs and stories both to study shifts in language, and to give identity to a concept of “German-ness” as diverse regions were newly joined together, and people were looking for a common history. But, this same impulse was used in dangerous ways — the nineteenth and then twentieth centuries used the idea of a Germanic Volk to inflict terrible atrocities. There are no Nazis without the idea of a German folk soul. And this sort of dividing line in definitions is seen throughout study of “folk” cultures. Even the association of Appalachian music with the tradition of English balladry was used with multiple agendas. For the people of Appalachia, it was a way of finding roots and longevity. For people from outside the region, it was often used as a way of furthering the idea of Appalachia as regressive and parochial (even going so far as to describe the people as being like English peasants from a century previous). Not only is this a condescending view of the poor white population of the region (which still persists to this day), it ignores the many influences on the region and the music. Not to mention the existence within both the region and the musical tradition of nonwhite people. Even the banjo, and instrument indelibly linked with this region and these songs, was originally created as part of Black culture, and was heavily tied into Black spirituality and rebellion. (For an interesting history of the banjo, allow me to recommend Well of Souls by Kristina R. Gaddy) ↩︎

- From “Ron Rash on Crime and Punishment in Appalachia,” posted on CrimeReads. As an aside: I definitely recommend reading anything by Ron Rash. His novels, short stories, and poetry are all stunningly written, and have a great deal of unflinching compassion for humanity. He is honestly my favorite writer. Though, full disclosure for readers of this blog: he does not really traffic in horror. The closest his writing comes to it is the gothic bend of Serena (wherein the eponymous character would not be out of place in a lineup with Rebecca De Winter, or Lady Macbeth). It, too, has something of a fairy tale bend, even if it is firmly set in a Depression-era logging community. Serena, The Cove, and Saints at the River are my personal top three. Also the poem “Abandoned Homestead in Watauga County” ↩︎

- From The Invention of Murder: How the Victorians Reveled in Death and Detection and Created Modern Crime by Judith Flanders. This is a really fascinating book. ↩︎

- “Murder in the Red Barn,” Tom Waits (from the album Bone Machine) ↩︎

- Vandaveer in fact released a whole album of murder ballads called Oh, Willie, Please… that has my favorite recordings of both “Omie Wise” and “Pretty Polly” ↩︎

- “Poor Ellen Smith,” Gillian Welch & David Rawlings (from the album All the Good Times) ↩︎

- It is surprisingly difficult to verify too many things about Ellen Smith. Not least because the varying stories and legends that grew around her murder erase any reference to her race, and the power imbalance that caused between her and her lover. Some sources instead explain the fact that Paul DeGraff did not marry her by calling her “simpleminded.” These are not pleasant implications. ↩︎

- “I’ll Tell You No Lies”: An Exploration of Trauma, Memory, and Violence in North Carolina Murder Ballads, Madison Ava Helm. ↩︎

- Crooked Still — a band I absolutely adore — does one of the most harshly moralizing versions of “Poor Ellen Smith”, which includes the line: “The men they will mourn you, their wives will be glad / such is the ending of a girl that is bad” ↩︎

- “I’ll Tell You No Lies”: An Exploration of Trauma, Memory, and Violence in North Carolina Murder Ballads, Madison Ava Helm. ↩︎

- From Rennie Sparks essay “Pretty Polly” in The Rose and the Briar: Death, Love and Liberty in the American Ballad, edited by Sean Wilentz and Greil Marcus ↩︎

- Another excellent recording, though the lyrics differ a little from those quoted here: “Pretty Polly,” Béla Fleck & Abigail Washburn ↩︎

I wish you could have heard my gasp when I saw the topic for this post! 😀 Murder ballads are such a fascinating subgenre of folk music and it was a treat to learn about their history! And now I need to go listen to some Doc Watson….

LikeLike

They’re such a fascinating topic! I think the hardest part was paring down my notes, and also limiting myself to just the murdered sweetheart ballads.

Also, I always support listening to Doc Watson…

LikeLike